© 2022 Vinnie Bagwell, sculptor, photograph by Donna Davis/Ms. Davis Photography

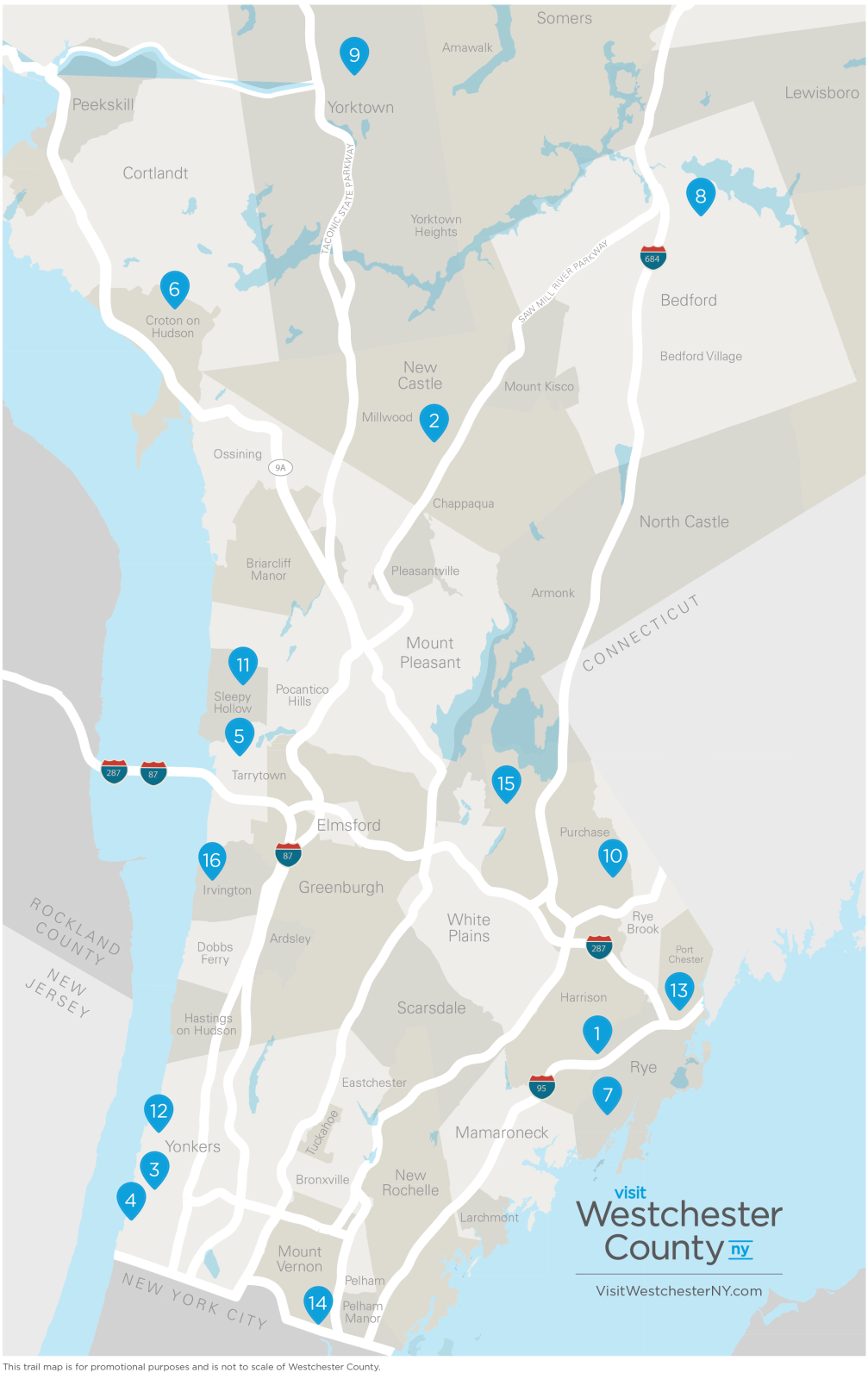

Westchester County Guide to African American History & Heritage

Forever Quilted in Our American Identity

Westchester has a long history as a home to African American culture. Learn about and explore historical sites, annual events, arts and culture and more.

Events

February is Black History Month, a time when people of all cultural backgrounds recognize the contributions African Americans have made to the United States through art, education, civil rights, and more. Westchester County joins in that recognition by hosting various lunches, school programs and other events to commemorate this important month.

An African American celebration of spring, Pinkster was historically held in the Hudson Valley as early as the 17th century. To the Dutch, Pinkster was a religious holiday. For their enslaved Africans, Pinkster was a time free from work and a chance to gather with family and friends. Filled with music, dance, food, and revelry, the cross-cultural festival is re-created each May with a rousing colonial-style celebration at Philipsburg Manor in Sleepy Hollow. Festivities include lively presentations of drumming and traditional dance, African folktales, and demonstrations of traditional African instruments and utilitarian wares.

Also known as “Freedom Day” or “Emancipation Day,” Juneteenth is a U.S. holiday that commemorates the announcement of the abolition of slavery in Texas in 1865. Events are held throughout the country on June 19; in Westchester County, parades and festivals take place in Peekskill and in White Plains.

Arts & Culture

African American cultural sites include the important collection of African art at the Neuberger Museum of Art in Purchase, and in Yonkers, the statue of Ella Fitzgerald and a public art project called the Enslaved Africans’ Rain Garden. On the waterfront near Philipse Manor Hall, this urban heritage garden includes six life-size bronze statues representing the six enslaved Africans living at the manor who, in 1787, were among the first to be freed in the United States—76 years before the Emancipation Proclamation.

In Croton, the Jack Peterson Memorial acknowledges a militiaman of African descent who in 1780 fired on a boat full of British soldiers attempting to come ashore. Peterson alerted officers at Fort Lafayette, who mobilized forces. A cannon greatly damaged the British ship, which was then unable to retrieve one of its commanders who had snuck ashore. The capture of this Major Andre led to the uncovering of the Benedict Arnold plot.

Also, there are numerous organizations in Westchester County that celebrate African American traditions including Youth Theatre Interactions in Yonkers, an after-school program that teaches young adults and children many different types of performing arts, including African dance and drumming.

1. African American Cemetery

The African American Cemetery was established in Rye when its site was deeded to the town on June 27, 1860, by Underhill and Elizabeth Halsted, “(to) be forever after kept and used for the purposes of a cemetery or burial place for the colored inhabitants of the said Town of Rye and its vicinity free and clear of any charge therefore.” In the latter part of his life, Underhill Halsted became a fervent follower of the Methodist movement, which was profoundly opposed to slavery. However, being anti-slavery did not mean one was not prejudiced. Such bias led African Americans to separate from the Methodist church and form their own Methodist organization, the African Methodist Episcopal AME Zion Church. The presence of two AME Zion churches in nearby Mamaroneck and Port Chester could have also motivated Halsted to gift the cemetery to local free persons of color.

The cemetery includes carved and dressed tombstones, with 35 indicating the interment of a war veteran. African American veterans of each of America’s armed conflicts from the Civil War through World War II are buried here. One such soldier was World War I veteran Francis M. Husted, who died in 1947. A former laborer, he was a member of the 370th Colored Regiment, the only unit in the U.S. Army with a full complement of African American officers from colonel to lieutenant. This unit was called the “Black Devils” by the Germans because of their courage and the “Partridges” by the French because of their proud bearing. In 1983, the African American Cemetery was listed as a Westchester County Tercentennial Historic Site, and in 2003 it was listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

Accessed through Greenwood Union Cemetery, 215 North Street, Rye. Open to the public.

2. Chappaqua Friends Meeting House

The Chappaqua Friends Meeting House, circa 1753, is the oldest Quaker meeting house standing in Westchester County. In the early 1750s, members of the Society of Friends, or Quakers, began to challenge the morality of slavery in colonial New York. In 1767, the Purchase community of Friends decreed that it was forbidden for its members to own enslaved people, stating that “[It] is not consistent with Christianity to buy or sell our fellow men for slaves.” The Society of Friends resolved that all of its members should release their enslaved people and seek to provide them with the means to support themselves and their families. The Quaker opposition to slavery served as a primary catalyst in its abolition in post–Revolutionary War New York.

420 Quaker Road, Chappaqua

(914) 238-3170

Open Sundays, 10:30 am–noon or by appointment.

3. Ella Fitzgerald Statue

Dubbed “The First Lady of Song,” Ella Fitzgerald (1917–1996) was the most popular female jazz singer in the United States for more than half a century. As an African American woman, she experienced not only the adulation of this country, but also some of its most hideous and persistent moral defects.

Raised in Yonkers, Ella lived and worked at a time when, for her, entrance to most white-owned clubs was through the back door. She literally conquered the bigoted, the insensitive and the racist with love through song while serving as an ambassador for both music and our country. African American artist Vinnie Bagwell created a bronze statue entitled “The First Lady of Jazz, Ella Fitzgerald” in her honor in 1996. It stands next to the Metro-North train station in Yonkers.

Yonkers Metro-North Railroad Station Plaza

5 Buena Vista Avenue, Yonkers

4. Enslaved Africans’ Rain Garden

The Enslaved Africans’ Rain Garden is an exhibition of five lifesize bronze sculptures depicting freed slaves. The sculptures, named “Themba the Boatman,” “I’Satta,” “Bibi,” “Sola” and “Olumide,” reside in a half-acre rain garden along the Hudson River esplanade in Yonkers. The installation allows guests to view the art from 360 degrees and appreciate the landscaped greenery of the work. The exhibition is the vision of Yonkers Artist Vinnie Bagwell. It is focused on remembering the lives, feelings and the legacy of men, women and children who were stripped of their human rights and were among the first to be manumitted/freed by law 64 years before the Emancipation Proclamation.

20 Water Grant Street, along the Yonkers waterfront

enslavedafricansraingarden.org

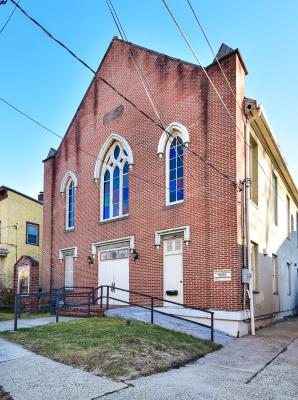

5. Foster Memorial AME Zion Church

Amanda and Henry Foster, the Reverend Jacob Thomas and Hiram Jimerson founded Foster Memorial African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Zion Church, a stop on the Underground Railroad, in Tarrytown in 1860. Amanda Foster, born in Albany in 1807, is considered the “Mother of the Church.” She was the driving force in the formation of the congregation, whose first meetings were held in her Tarrytown confectionery. In possession of her “free papers,” documents that permitted African Americans prior to the abolishment of slavery to freely travel, Amanda obtained employment as a nurse to the children of the governor of Arkansas. While in Arkansas, she contributed to the Underground Railroad movement by using her “free papers” to help a young, female fugitive escape from enslavement. Foster moved back to New York in 1837. During the Civil War, members of Foster AME Zion helped provide food and shelter to people escaping enslavement to Canada.

Like most AME Zion churches, Foster AME Zion was and still is a religious and social crossroads for the African American community, providing a meeting place for worship and a place for public interaction and service. In 1982, the church was listed in the National Register of Historic Places. It was recognized as a Westchester County Tricentennial Historic Site in 1983.

90 Wildey Street, Tarrytown

Open to the public.

Call (914) 909-4618 for additional information.

6. Jack Peterson Memorial

The Jack Peterson Memorial acknowledges a militiaman of African descent who, in 1780, fired on a boat full of British soldiers attempting to come ashore. Peterson alerted officers at Fort Lafayette, who mobilized forces. A cannon greatly damaged the British ship, which was then unable to retrieve one of its commanders who had snuck ashore. The capture of this Major Andre led to the uncovering of the Benedict Arnold plot.

Croton Point Park

1A Croton Point Ave., Croton-on-Hudson

7. Jay Heritage Center at the Jay Estate

The Jay Heritage Center occupies the site of the home of Founding Father, peacemaker and jurist John Jay. Archaeology shows it was also the home and burial site of several generations of people, both free and enslaved, who worked for the Jay family. We know many of their names—Mary, Clarinda, Plato and Peet. One man, Caesar Valentine, inspired the very first significant African American character in an American novel—James Fenimore Cooper’s book, “The Spy.”

Jay was a founder and president of the Manumission Society of New York, which advocated abolition of slavery and the transatlantic slave trade; he also helped established the first African Free Schools to educate children of emancipated men and women. As governor of New York, Jay signed the Gradual Emancipation Act into law in 1799.

Jay’s son, Peter Augustus, was profoundly anti-slavery and also served as president of the Manumission Society. As a delegate to the New York Constitutional Convention of 1821, he called for the extension of suffrage to African Americans in one of the most eloquent speeches of the convention.

The Jay Estate hosts a full calendar of programs related to African American history. The Trailblazers Awards Ceremony is held at the site annually. The venue is also the home of the acclaimed interactive play “Striving for Freedom,” which is offered for free to all middle schools in Westchester County; bus transportation for this cultural field trip is also free through New York State Parks.

210 Boston Post Road, Rye

(914) 698-9275

1838 Jay Mansion

April 1–October 31, Sun. 2–5 pm; other times by appointment.

Free admission.

1907 Carriage House Visitor Center

Jun. 1–Sept. 30,

Wed.–Fri. 10 am–4 pm; Oct. 1–May 31, Wed.–Thurs. 10 am–4 pm.

Free admission.

8. John Jay Homestead State Historic Site

After growing up in the Westchester community of Rye, Founding Father John Jay helped to establish a homestead for himself and his family in the northern Westchester community of Bedford. Enslaved and free Africans lived and worked at Jay properties in Bedford, New York City, Albany, Fishkill and Rye throughout the 18th and early 19th centuries.

John Jay Homestead is a National Historic Landmark and is operated by the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. The Education and Visitor Center includes a main exhibit gallery with a welcome desk and gift shop, a map-model of the property, computer kiosks with exhibit content and period news magazines featuring articles relevant to John Jay’s life. A 2011 addition to the building features a video viewing area, an activity center with a replica governess’s cart similar to one the Jay children rode in, and discovery boxes full of interesting items. Around the corner in the horse stalls, visitors can see realistic models of horses and experience a sound and light show emphasizing the importance of horses to the Jay family and Bedford Farm.

400 Jay Street/Route 22, Katonah

(914) 232-8119 or (914) 232-5651

Grounds open year-round, sunrise to sunset. Free admission. Tours Wed. through Sun., May to Oct.; Thurs. through Sat., Nov. to Apr.

Adults $10, seniors and students $7, members and children under 12 free.

9. Monument to First Rhode Island Regiment

Erected in 1982 as a result of the pioneering research and activism of John H. Harmon, this monument is dedicated to the valiant and courageous soldiers of the First Rhode Island Regiment, which was composed predominantly of enslaved African American soldiers who had enlisted in the American Continental Army to earn their freedom. During the American Revolution, these men fought courageously to defend American liberty against the aggressions of British tyranny. Several dozen soldiers of the regiment were killed and wounded at the Battle of Pines Bridge in Yorktown on May 14, 1781.

First Presbyterian Church (Burial Grounds)

2880 Crompond Road, Yorktown Heights

(914) 245-2186

Open to the public. Parking available.

10. The Neuberger Museum of Art, the African Art Collection

African art has been an integral part of the Neuberger Museum of Art since it opened in 1974. In 1999, the collection almost doubled in size with the major gift of 153 works from the collection of the late Lawrence Gussman, a notable collector and a resident of Scarsdale, New York. Gussman’s interest in Africa began in 1957 when he met Dr. Albert Schweitzer at his hospital in Labaréné (Gabon).

The collection is strongest in the arts of central Africa. However, major objects offer artistic insights into more than 30 cultures and span a geographic area from Mali to Mozambique.

735 Anderson Hill Road, Purchase

(914) 251-6100

Wed. noon–8 pm (fall and spring semesters), Thurs.–Sun. noon–5 pm.

Adults $5, seniors $3, members, children under 12 and active-duty/military personnel free.

Nigeria, Yoruba peoples, Bamgboye and his workshop Dance Headdress (epa) ca. 1940; Wood and pigment47.5 x 18 x 18 inches; Collection of the Neuberger Museum

of Art, Purchase College, State University of New York; Gift of Eliot Hirshberg from the Aimee W. Hirshberg Collection of African Art; Photo credit: Jim Frank

11. Philipsburg Manor

Philipsburg Manor, a property of Historic Hudson Valley, is a nationally significant late 17th and early 18th-century milling and trading complex that was part of a vast 52,000-acre estate owned by the Anglo-Dutch Philipse family. Enslaved individuals of African descent operated the commercial center of the estate in what is now the village of Sleepy Hollow.

Today, costumed interpreters demonstrate and talk about various aspects of colonial life that affected the culture and economy of those who lived and labored at Philipsburg Manor. The interpreters offer regular performances of vignettes dramatizing aspects of enslavement of Africans. In addition, the site offers popular school programs and a lively calendar of special events. Visitors experience hands-on tours of the water-powered gristmill, manor house, barn, activity center and slave garden. The visitor center includes a shop and cafe.

Route 9, Sleepy Hollow

(914) 366-6900 Mon.–Fri; (914) 631-3992 weekends

Early May–mid-Nov. Wed.–Sun. Timed tours only from 10:30 am–3 pm (3:30 pm Sat.–Sun. and holidays). Adults $12, seniors (65+) $10, students (18–25) $10, children 3–17 $6, members and children under 3 free; add $2 surcharge if tickets are purchased onsite or by phone.

12. Philipse Manor Hall State Historic Site

Philipse Manor Hall, listed in the National Register of Historic Places, was a major component of the original Philipsburg Manor and served as its Lower Mill complex. As master of Philipsburg Manor, Frederick Philipse, along with his wife, Margaret Hardenbroeck, were Westchester’s premier examples of 17th-century large-scale New York holders of enslaved people. They were deeply involved in both the trading and holding of enslaved people.

Prior to the Revolutionary War, several generations of the Philipse family were leading merchants in New York’s commercial life. The records of their businesses and lives indicate that enslaved Africans were vital to their success and the development of Westchester.

The Philipses’ global commercial activities placed Westchester at the center of the “Golden Circuit,” better known as the transatlantic and Indian Ocean slave trade to the West Indies, America and Europe.

29 Warburton Avenue at Dock Street, Yonkers

(914) 965-4027

Tues.–Sat. from Apr. to Oct., noon–4:30 pm; Tues.–Sat. from Nov. to Mar., noon–3:30 pm. Adults $5, seniors and students $3, children under 12 free.

13. St. Frances AME Zion Church

St. Frances African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Zion Church is the oldest African American church and one of the oldest of all denominations in Port Chester. It was founded in 1849 by a group of residents of Port Chester, Mamaroneck and New Rochelle who met for prayer at the home of the Banks family on South Main Street. Services were guided by a circuit preacher, Father Tappan. As their congregation grew, they moved to King Street, and in 1856 Rev. Jephthah Barcroft became their first full-time pastor. Two iterations of the church were destroyed by fire before the current building was erected in 1889 on the site of a former schoolhouse. Named for its largest benefactor, Mrs. Frances Quintard, the church continues to be a vibrant community center and will celebrate its 175th anniversary in 2024.

During the 19th and 20th centuries, the church often hosted gatherings of the AME Zion Church’s New York Conference. Generations of trustees of St. Frances were also longtime stewards of the historic Rye African Cemetery. Many members have been dynamic leaders in the Port Chester/Rye branch of the NAACP.

18 Smith Street, Port Chester

Open to the public.

(914) 939-1056 for additional information.

14. St. Paul’s Church National Historic Site

St. Paul’s Church, completed in 1787, is located in a portion of Mount Vernon that was once part of the town of Eastchester. Built along the old Boston Post Road, it rested in the midst of farmhouses and taverns.

The earliest reference to African Americans in Eastchester appears in the town records dated April 23, 1672. The entry records the sale of a “Negro woman” to Samuel Adams of Fairfield, Connecticut, by Moses Hoitte.

The church and taverns were the center of community life. Many of the 8,000 interred in the cemetery are persons of African descent, buried here in the 19th and 20th centuries. The church records include the sexton’s book and burial records denoting the race of those interred in the historic graveyard. A particular program focus is the journey from slavery to freedom of Rebecca Turner, an African American woman who became an independent landowner of property abutting the church; she is interred in the cemetery.

897 South Columbus Avenue, Mount Vernon

(914) 667-4116

Grounds open to the public. Mon.–Fri. from Jan. to Jun., 9 am–5 pm; Tues.–Sat. from Jul. to Dec., 9 am–5 pm plus the second Sat. of each month noon–4 pm.

15. Stony Hill Cemetery

Post–Revolutionary War people emancipated from slavery settled in the rough and stony hills where Harrison, North Castle and White Plains meet near Silver Lake. Their community, also known as “The Hills,” was evidence of an emerging free African American class in early Westchester County.

The community’s presence and involvement in county life is recorded in various documents, as many of its residents were literate and left records of their world view in the form of letters and poems to family members.

Stony Hill Cemetery is the last remaining identifiable element of “The Hills.” The property on which the 6.5-acre cemetery sits was part of a land grant given by the Purchase Friends (Quakers) to enslaved people they voluntarily freed in the 18th century. Approximately 200 of “The Hills” residents, including 12 African American Civil War veterans, are buried in the cemetery.

Today, the area is surrounded by residential development. Mt. Hope AME Zion Church in White Plains and the Stony Hill Cemetery Committee serve as the stewards of this historic site and represent the voice for one of the first free black communities in this country. The committee honors fallen heroes through beautification efforts and ongoing research of the site’s history.

Buckout Road, Harrison

Open to the public. Parking limited.

16. Villa Lewaro

Madam C.J. Walker, born Sarah Breedlove in Louisiana, was the daughter of enslaved parents. She invented, patented and brilliantly marketed hair and cosmetics for women of color. Walker’s success made her one of the first African American millionaires. In 1916, Madam Walker commissioned the design and construction of Villa Lewaro.

The mansion is an astounding testimony to the genius of Vertner W. Tandy, New York’s first certified black architect. The 32-room mansion includes exquisite stained-glass windows, vaulted ceilings, marble staircases and intricate ceiling moldings.

Villa Lewaro was placed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1976. In the 1990s, the mansion was to be demolished to redevelop the property, but lobbying by preservationists saved it. An African American entrepreneur later purchased the mansion and restored it to its former splendor. In 2018 Villa Lewaro was purchased by Richelieu Dennis, who immigrated to the U.S. from Liberia and is the founder of Sundial Brands, which manufactures Madam C.J. Walker Beauty Culture products.

67 North Broadway, Irvington

Private residence. Not open to the public; historic marker on Broadway.

To order your free copy of the African American Heritage Brochure, please click here.

Photography by Kim Crichlow.

Enslaved Africans' Rain Garden Photo by Donna Davis/Ms. Davis Photography